Source: Articles on Smashing Magazine — For Web Designers And Developers | Read More

Designing for mental health means designing for vulnerability. Empathy-Centred UX becomes not a “nice to have” but a fundamental design requirement. Here’s a practical framework for building trust-first mental health products.

Imagine a user opening a mental health app while feeling overwhelmed with anxiety. The very first thing they encounter is a screen with a bright, clashing colour scheme, followed by a notification shaming them for breaking a 5-day “mindfulness streak,” and a paywall blocking the meditation they desperately need at that very moment. This experience isn’t just poor design; it can be actively harmful. It betrays the user’s vulnerability and erodes the very trust the app aims to build.

When designing for mental health, this becomes both a critical challenge and a valuable opportunity. Unlike a utility or entertainment app, the user’s emotional state cannot be treated as a secondary context. It is the environment your product operates in.

With over a billion people living with mental health conditions and persistent gaps in access to care, safe and evidence-aligned digital support is increasingly relevant. The margin for error is negligible. Empathy-Centred UX becomes not a “nice to have” but a fundamental design requirement. It is an approach that moves beyond mere functionality to deeply understand, respect, and design for the user’s intimate emotional and psychological needs.

But how do we translate this principle into practice? How do we build digital products that are not just useful, but truly trustworthy?

Throughout my career as a product designer, I’ve found that trust is built by consistently meeting the user’s emotional needs at every stage of their journey. In this article, I will translate these insights into a hands-on empathy-centred UX framework. We will move beyond theory to dive deeper into applicable tools that help create experiences that are both humane and highly effective.

In this article, I’ll share a practical, repeatable framework built around three pillars:

Together, these pillars offer a grounded way to design mental health experiences that prioritise trust, emotional safety, and real user needs at every step.

Onboarding is “a first date” between a user and the app — and the first impression carries immense stakes, determining whether the user decides to continue engaging with the app. In mental health tech, with up to 20,000 mental-health-related apps on the market, product designers face a dilemma of how to integrate onboarding’s primary goals without making the design feel too clinical or dismissive for a user seeking help.

The Empathy ToolIn my experience, I have found it essential to design onboarding as the first supportive conversation. The goal is to help the user feel seen and understood by delivering a small dose of relief quickly, not just overload them with data and the app’s features.

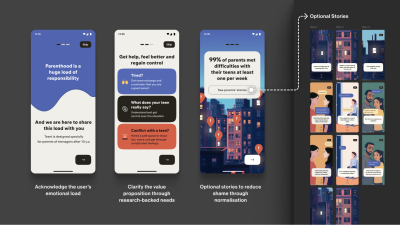

At Teeni, an app for parents of teenagers, onboarding requires an approach that solves two problems: (1) acknowledge the emotional load of parenting teens and show how the app can share that load; (2) collect just enough information to make the first feed relevant.

Interviews surfaced a recurring feeling among parents: “I’m a bad parent, I’ve failed at everything.” My design idea was to provide early relief and normalisation through a city-at-night metaphor with lit windows: directly after the welcome page, a user engages with three brief, animated and optional stories based on frequent challenges of teenage parenting, in which they can recognise themselves (e.g., a story of a mother learning to manage her reaction to her teen rolling their eyes). This narrative approach reassures parents that they are not alone in their struggles, normalising and helping them cope with stress and other complex emotions from the very beginning.

Note: Early usability sessions indicated strong emotional resonance, but post-launch analytics showed that the optionality of the storytelling must be explicit. The goal is to balance the storytelling to avoid overwhelming the distressed parent, directly acknowledging their reality: “Parenting is tough. You’re not alone.”

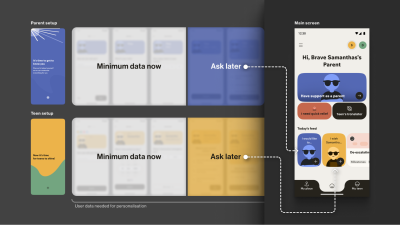

To tailor guidance to each family, we defined the minimal data needed for personalisation. On the first run, we collect only the essentials for a basic setup (e.g., parent role, number of teens, and each teen’s age). Additional, yet still important, details (specific challenges, wishes, requests) are gathered gradually as users progress through the app, avoiding long forms for those who need support immediately.

The entire onboarding is centred around a consistently supportive choice of words, turning a typically highly practical, functional process into a way to connect with the vulnerable user on a deeper emotional level, while keeping an explicit fast path.

This initial conversation sets the stage for trust. But this trust is fragile. The next step is to ensure the app’s very environment doesn’t break it.

A user experiencing anxiety or depression often shows reduced cognitive capacity, which affects their attention span and the speed with which they process information and lowers tolerance for dense layouts and fast, highly stimulating visuals. This means that high-saturation palettes, abrupt contrast changes, flashing, and dense text can feel overwhelming for them.

The Empathy ToolWhen designing a user flow for a mental health app, I always apply the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.2 as a foundational baseline. On top of that, I choose a “low-stimulus”, “familiar and safe” visual language to minimise the user’s cognitive load and create a calm, predictable, and personalised environment. Where appropriate, I add subtle, opt-in haptics and gentle micro-interactions for sensory grounding, and offer voice features as an option in high-stress moments (alongside low-effort tap flows) to enhance accessibility.

Imagine you need to guide your users “by the hand”: we want to make sure their experience is as effortless as possible, and they are quickly guided to the support they need, so we avoid complicated forms and long wordings.

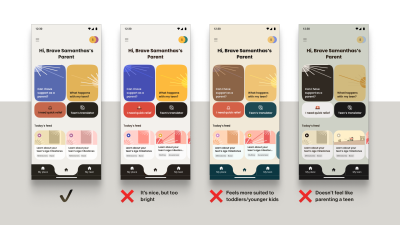

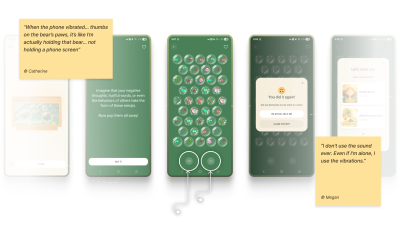

For the app focused on instant stress relief, Bear Room, I tested a “cosy room” design. My initial hypothesis was validated through a critical series of user interviews: the prevailing design language of many mental health apps appeared misaligned with the needs of our audience. Participants grappling with conditions such as PTSD and depression repeatedly described competing apps as “too bright, too happy, and too overwhelming,” which only intensified their sense of alienation instead of providing solace. This suggested a mismatch for our segment, which instead sought a sense of safety in the digital environment.

This feedback informed a low-arousal design strategy. Rather than treating “safe space” as a visual theme, we approached it as a holistic sensory experience. The resulting interface is a direct antithesis to digital overload; it gently guides the user through the flow, keeping in mind that they are likely in a state where they lack the capacity to concentrate. The text is divided into smaller parts and is easily scannable and quickly defined. The emotional support tools — such as a pillow — are highlighted on purpose for convenience.

The interface employs a carefully curated, non-neon, earthy palette that feels grounding rather than stimulating, and it rigorously eliminates any sudden animations or jarring bright alerts that could trigger a stress response. This deliberate calmness is not an aesthetic afterthought but the app’s most critical feature, establishing a foundational sense of digital safety.

To foster a sense of personal connection and psychological ownership, the room introduces three opt-in “personal objects”: Mirror, Letter, and Frame. Each invites a small, successful act of contribution (e.g., leaving a short message to one’s future self or curating a set of personally meaningful photos), drawing on the IKEA effect (PDF).

For instance, Frame functions as a personal archive of comforting photo albums that users can revisit when they need warmth or reassurance. Because Frame is represented in the digital room as a picture frame on the wall, I designed an optional layer of customisation to deepen this connection: users can replace the placeholder with an image from their collection — a loved one, a pet, or a favourite landscape — displayed in the room each time they open the app. This choice is voluntary, lightweight, and reversible, intended to help the space feel more “mine” and deepen attachment without increasing cognitive load.

Note: Always adapt to the context. Try to avoid making the colour palette too pastel. It is useful to balance the brightness based on the user research, to protect the right level of the app’s contrast.

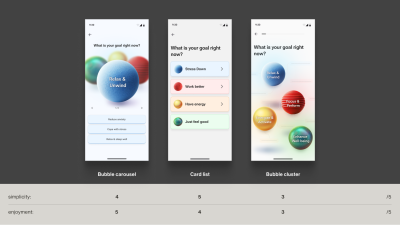

In Food for Mood, I used a visual metaphor: coloured bubbles representing goals and emotional states (e.g., a dense red bubble for “Performance”). This allows users to externalise and visualise complex feelings without the cognitive burden of finding the right words. It’s a UI that speaks the language of emotion directly.

In an informal field test with young professionals (the target audience) in a co-working space, participants tried three interactive prototypes and rated each on simplicity and enjoyment. The standard card layout scored higher on simplicity, but the bubble carousel scored better on engagement and positive affect — and became the preferred option for the first iteration. Given that the simplicity trade-off was minimal (4⁄5 vs. 5⁄5) and limited to the first few seconds of use, I prioritised the concept that made the experience feel more emotionally rewarding.

Adding a touch of tactile micro-interactions like bubble-wrap popping in Bear Room, may also offer users moments of kinetic relief. Integrating deliberate, tactile micro-interactions, such as the satisfying bubble-wrap popping mechanic, provides a focused act that can help an overwhelmed user feel more grounded. It offers a moment of pure, sensory distraction for a person stuck in a torrent of stressful thoughts. This isn’t about gamification in the traditional, points-driven sense; it’s about offering a controlled, sensory interruption to the cycle of anxiety.

Note: Make tactile effects opt-in and predictable. Unexpected sensory feedback can increase arousal rather than reduce it for some users.

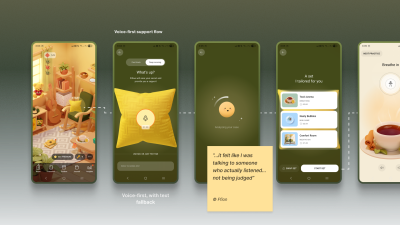

When a user is in a state of high anxiety or depression, it can become an extra effort for them to type something in the app or make choices. In moments when attention is impaired, and a simple, low-cognitive choice (e.g., ≤4 clearly labelled options) isn’t enough, voice input can offer a lower-friction way to engage and communicate empathy.

In both Teeni and Bear Room, voice was integrated as a primary path for flows related to fatigue, emotional overwhelm, and acute stress — always alongside a text input alternative. Simply putting feelings into words (affect labelling) has been shown to reduce emotional intensity for some users, and spoken input also provides a richer context for tailoring support.

For Bear Room, we give users a choice to share what’s on their mind via a prominent mic button (with text input available below. The app then analyses their response with AI (does not diagnose) and provides a set of tailored practices to help them cope. This approach gives users a space for the raw, unfiltered expression of emotion when texting feels too heavy.

Similarly, Teeni’s “Hot flow” lets parents vent frustration and describe a difficult trigger via voice. Based on the case description, AI gives a one-screen piece of psychoeducational content, and in a few steps, the app suggests an appropriate calming tool, uniting both emotional and relational support.

Note: Mental-health topics are highly sensitive, and many people feel uncomfortable sharing sensitive data with an app — especially amid frequent news about data breaches and data being sold to third parties. Before recording, show a concise notice that explains how audio is processed, where it’s processed, how long it’s stored, and that it is not sold or shared with third parties. Present this in a clear, consent step (e.g., GDPR-style). For products handling personal data, it’s also best practice to provide an obvious “Delete all data” option.

A safe interface builds trust in the moment. The final pillar is about earning the trust that brings users back, day after day.

Encouraging consistent use without manipulation often requires innovative solutions in mental health. The app, as a business, faces an ethical dilemma: its mission is to prioritise user wellbeing, which means it cannot indulge users simply to maximise their screen time. Streaks, points, and time limits can also induce anxiety and shame, negatively affecting the user’s mental health. The goal is not to maximise screen time, but to foster a supportive rhythm of use that aligns with the non-linear journey of mental health.

The Empathy ToolI replace anxiety-inducing gamification with retention engines powered by empathy. This involves designing loops that intrinsically motivate users through three core pillars: granting them agency with customisable tools, connecting them to a supportive community, and ensuring the app itself acts as a consistent source of support, making return visits feel like a choice, not a chore or pressure.

In search of reimagining retention mechanics away from punitive streaks and towards a model of compassionate encouragement, the Bear Room team came up with the idea of the so-called “Key” economy. Unlike a streak that shames users for missing a day, users are envisioned to earn “keys” for logging in every third day — a rhythm that acknowledges the non-linear nature of healing and reduces the pressure of daily performance. Keys never gate SOS sets or essential coping practices. Keys only unlock more objects and advanced content; the core toolkit is always free. The app should also preserve users’ progress regardless of their level of engagement.

The system’s most empathetic innovation, however, lies in the ability for users to gift their hard-earned keys to others in the community who may be in greater need (still in the process of making). This intends to transform the act of retention from a self-focused chore into a generous, community-building gesture.

It aims to foster a culture of mutual support, where consistent engagement is not about maintaining a personal score, but about accumulating the capacity to help others.

Why it Works

Within Bear Room, users can write and receive supportive letters anonymously to other users around the world. This tool leverages AI-powered anonymity to create a safe space for radical vulnerability. It provides a real human connection while completely protecting user privacy, directly addressing the trust deficit. It shows users they are not alone in their struggles, a powerful retention driver.

Note: Data privacy is always a priority in product design, but (again) it’s crucial to approach it firsthand in mental health. In the case of the letter exchange, robust anonymity isn’t just a setting; it is the foundational element that creates the safety required for users to be vulnerable and supportive with strangers.

The “Teenager Translator” in Teeni became a cornerstone of our retention strategy by directly addressing the moment of crisis where parents were most likely to disengage. When a parent inputs their adolescent’s angry words like “What’s wrong with you? It’s my phone, I will watch what I want, just leave me alone!”, the tool instantly provides an empathetic translation of the emotional subtext, a de-escalation guide, and a practical script for how to respond.

This immediate, actionable support at the peak of frustration transforms the app from a passive resource into an indispensable crisis-management tool. By delivering profound value exactly when and where users need it most, it creates powerful positive reinforcement that builds habit and loyalty, ensuring parents return to the app not just to learn, but to actively navigate their most challenging moments.

Let’s return to the overwhelmed user from the introduction. They open an app that greets them with a tested, audience-aligned visual language, a validating first message, and a retention system that supports rather than punishes.

This is the power of an Empathy-Centred UX Framework. It forces us to move beyond pixels and workflows to the heart of the user experience: emotional safety. But to embed this philosophy in design processes, we need a structured, scalable approach. My designer path led me to the following three core pillars:

While we, as designers, don’t directly define the app’s success metrics, we cannot deny that our work influences the final outcomes. This is where our practical tools in mental health apps may come in partnership with the product owner’s goals. All the tools are designed based on hypotheses, evaluations of whether users need them, further testing, and metric analysis.

I would argue that one of the most critical success components for a mental health app is trust. Although it is not easy to measure, our role as designers lies precisely in creating a UX Framework that respects and listens to its users and makes the app fully accessible and inclusive.

The trick is to achieve a sustainable balance between helping users reach their wellness goals and the gaming effect, so they also benefit from the process and atmosphere. It is a blend of enjoyment from the process and fulfillment from the health benefits, where we want to make a routine meditation exercise something pleasant. Our role as product designers is to always keep in mind that the end goal for the user is to achieve a positive psychological effect, not to remain in a perpetual gaming loop.

Of course, we need to keep in mind that the more responsibility the app takes for its users’ health, the more requirements there arise for its design.

When this balance is struck, the result is more than just better metrics; it’s a profound positive impact on your users’ lives. In the end, empowering a user’s well-being is the highest achievement our craft can aspire to.